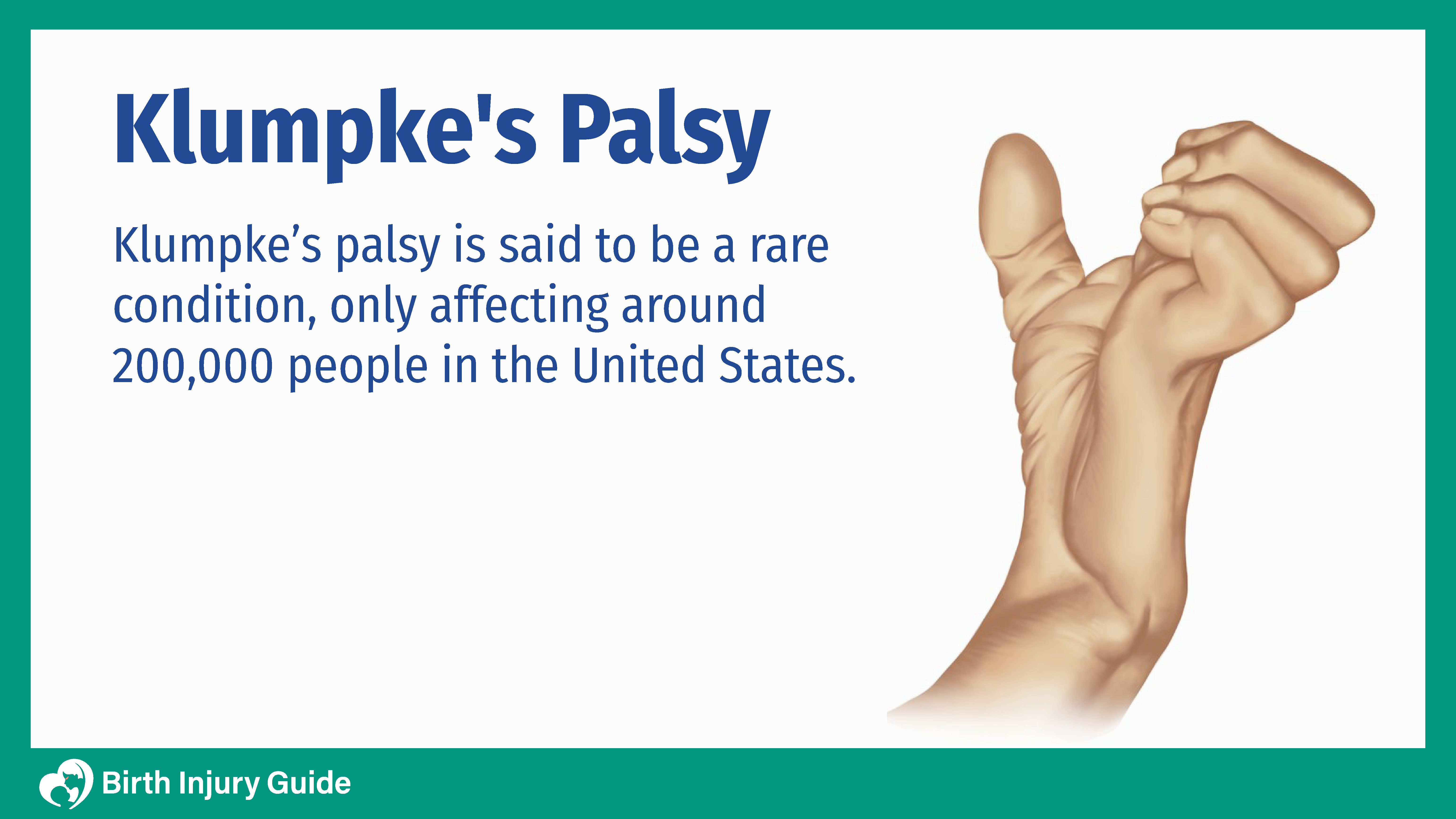

Klumpke’s Palsy

Klumpke’s palsy is a form of brachial plexus injury as it affects the lower portion of the brachial plexus nerves. The brachial plexus nerves are a network of five nerves that control the back of the neck, the armpit and the upper limbs. Klumpke’s palsy affects the lower two of these nerves, causing paralysis in the forearm and the hand. The wrist flexors may also be involved.

What is Klumpke’s Palsy?

Klumpke’s palsy is a type of neuropathy involving the brachial plexus. This condition involves nerves that are compromised. It often causes numbness or loss of sensation, pain and discomfort. It can also cause mobility issues in the affected arm.

Nerves are very sensitive and the paralysis of Klumpke’s palsy can affect a child even if the nerves are only slightly damaged. There are different degrees of damage, however:

- Avulsion is the most severe form in which the nerve is actually torn from the spine.

- Rupture occurs when the nerve has been torn but not at the spinal connection.

- A ‘pinched nerve’ is when the nerve has torn but it has healed itself and the scar tissue pressures the nerve unduly.

- Neuropraxia or stretching occurs when the nerve has been damaged but not torn.

All degrees can cause sensitivity and paralysis.

What Causes Klumpke’s Palsy?

Klumpke’s palsy happens most commonly due to a condition called shoulder dystocia. Shoulder dystocia occurs when the baby is delivered vaginally and the shoulder gets caught on the mother’s pubic bone. There are several risk factors for shoulder dystocia, such as:

- The baby is proportionately too big for the birth canal (cephalo-pelvic disproportion, called CPD) causing the baby’s head to turn abnormally from his or her shoulder.

- The strain of being pushed through the birth canal uncomfortably.

- The baby is born face first (causing the neck undue harm from being pulled out that way).

- The baby is born feet first (and the arms come out above the baby’s head).

Symptoms of Klumpke’s Palsy

Even the slightest nerve damage can result in numbness or loss of feeling for your child anywhere in the forearm, wrist, or hand.

However, symptoms are generally more severe, and because the child is usually unable to move his or her forearm, hand, and possibly wrist flexors, the child will appear to have a claw-like hand. If Klumpke’s palsy is related to Horner’s Syndrome, the child will also have a miosis (constricted pupil) in the affected eye.

Tests to Confirm a Klumpke’s Palsy Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing Klumpke’s palsy is a physical examination. Your doctor will evaluate your child’s arm and hand strength and will note any additional symptoms. Next, he or she may perform tests to confirm the diagnosis. Such tests may include:

- Electromyogram (EMG): Measures electrical activity in a certain muscle in response to stimulation.

- Imaging Studies: Doctors may request an X-ray, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Nerve Conduction Studies: Measures how well individual nerves send electrical signals from the spinal cord to muscles.

Treatment for Klumpke’s Palsy

Sometimes nerves heal on their own. If a child experiences paralysis due to neuroma (when the nerve has healed itself but the scar tissue still interferes with normal electrical communication), surgery may be required to repair that nerve so that it can heal cleanly.

For the nerves that don’t heal on their own, surgery may be an option. Generally all children that experience any form of brachial plexus nerve damage have to go through physical therapy so that they can bring exercise and blood flow to the area and to build up the responsive muscles.

Prognosis for Klumpke’s Palsy

Healing from Klumpke’s palsy can take anywhere from three to four months to two years. The good news is that the prognosis for children with this birth injury is very good. Children are generally expected to have a 90-100 percent recovery rate.